Voting Method Simulations for Investigating Voter Satisfaction Maximization¶

John Huang, 5 February 2021

Executive Summary¶

These reports document election simulation results using the votesim Python package. Source code can be found on Github. The objective of these simulations is to determine an ideal voting method to replace first-past-the-post (FPTP), or plurality, voting as practiced in the United States. These simulations attempt to measure the ability of a voting method to choose a candidate that maximally satisfies the electorate, through preference distance minimization. Although computer simulations are limited in their ability to realistically simulate human voting behavior, they are still useful tools in determining the theoretical ideal efficiency and reliability of a system when assuming rational agents.

Several different voting systems were assessed and compared to traditional plurality, first-past-the-post (FPTP) voting. The assessed voting systems include

Top-two Runoff

First-past-the-post (FPTP), or plurality voting

Condorcet-compliant Smith-minimax

Condorcet-complaint Ranked Pairs

Voting method performance is measured using “Voter Satisfaction Efficiency (VSE)” , a metric devised to measure the utilitarian performance of a voting method. In this metric, 100% VSE symbolizes the election of an ideal, maximally satisfactory candidate. 0% VSE symbolizes the election of an average, middle-of-pack candidate that when averaged over many elections, is equivalent to random candidate selection.

These results show simulations for honest voting as well as strategic voting. A simple metric which averaged the performance of honest, 1-sided strategy, and 2-sided strategy was used to devise performance scores in the table below:

Election Method |

Average VSE |

|---|---|

plurality |

0.515 |

top_two |

0.683 |

irv |

0.725 |

score |

0.762 |

approval50 |

0.772 |

maj_judge |

0.812 |

ranked_pairs |

0.849 |

smith_minimax |

0.850 |

star5 |

0.858 |

smith_score |

0.870 |

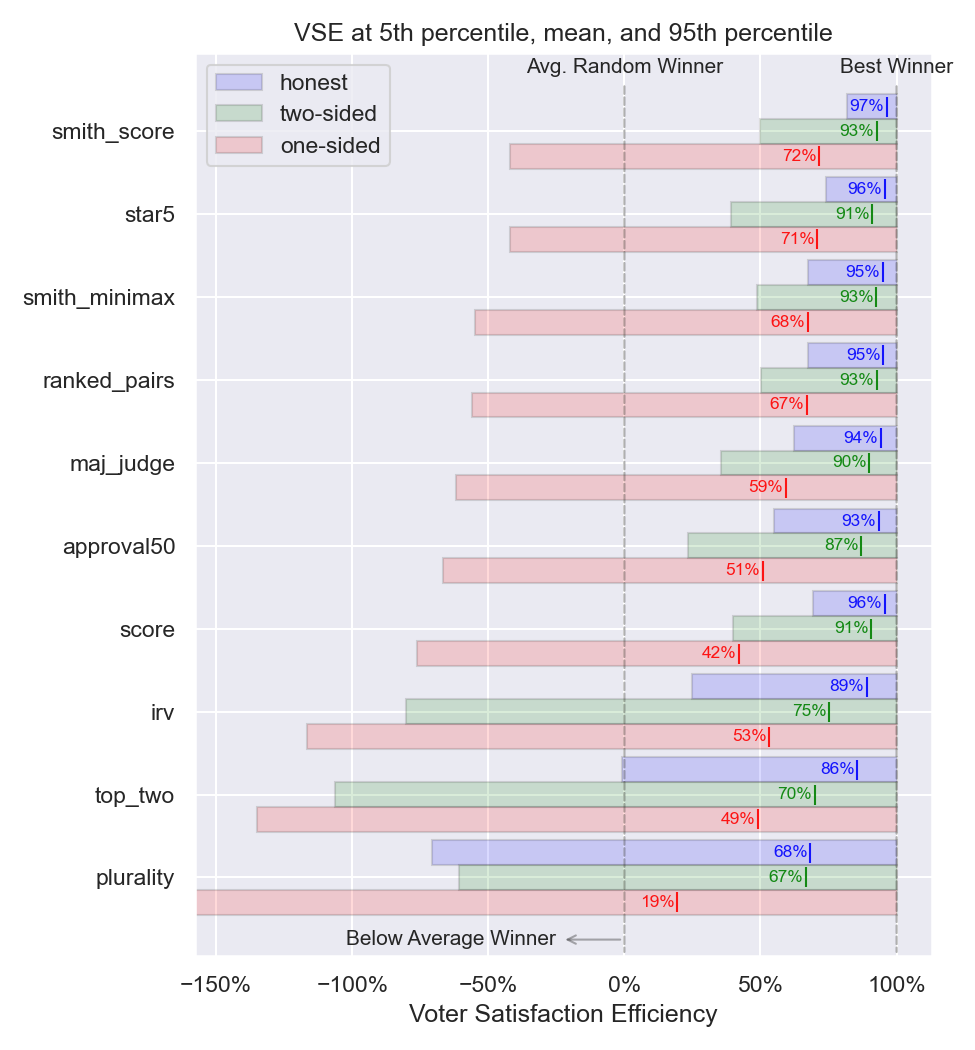

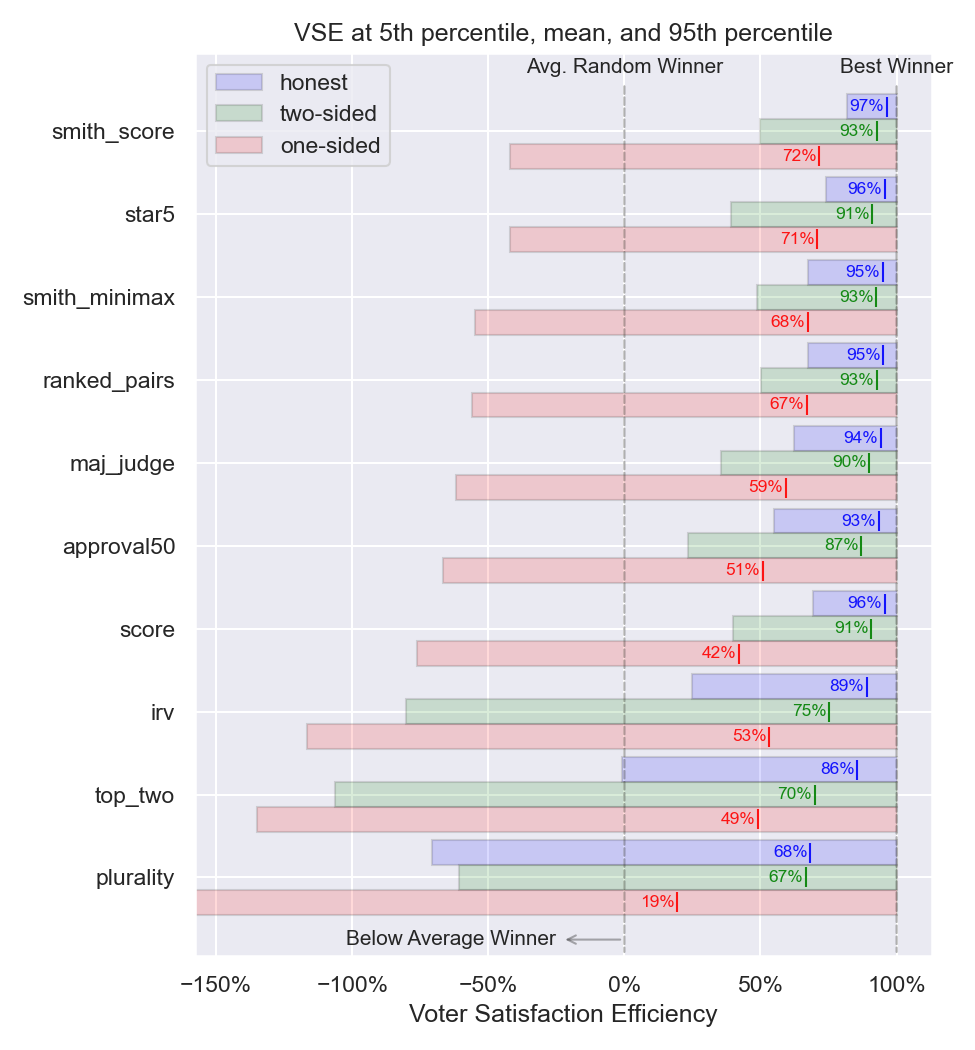

VSE results are also plotted, breaking down three strategy assumptions made in the simulations - honest strategy, one-sided strategy, and two-sided strategy. Results are plotted for the 5th percentile of worst VSE, the mean VSE, and the 95th percentile of best VSE.

Figure 1: Voter satisfaction efficiency for honest, one-sided, and two-sided strategy¶

This report ultimately finds that several methods have excellent performance in their ability to choose candidates which satisfy a greater number of voters than other methods. These best methods include Condorcet-compliant methods, STAR voting, and Smith-Score. Among the highest performing methods, STAR voting is the simplest to implement and compute.

Election Methods¶

In the United States, FPTP plurality voting is commonly practiced for local, state, Congressional, and presidential elections. However several alternatives have been proposed which will be described here.

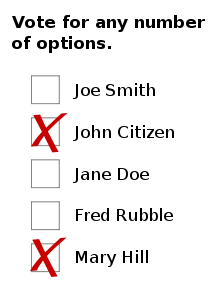

Approval Voting - In approval voting, voters may select any number of candidates but may only select two options – approve or disapprove. An example ballot is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 2: Approval voting ballot¶

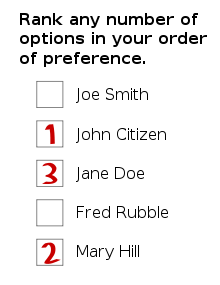

Instant runoff voting (IRV) – Also known as “Ranked Choice Voting”, instant runoff allows voters to rank candidates from first to last. To select the winner, instant runoff eliminates candidates one-by-one based on who receives the fewest top-choice votes. The eliminated candidate’s votes are then added to the total of their next choice. An example ranked ballot is shown in Figure 2. In this report the name IRV is used rather than ranked choice to distinguish IRV from other ranked voting methods that have been assessed.

Figure 3: Ranked voting ballot used for IRV and Condorcet methods¶

Condorcet – Condorcet methods are a family of voting systems that allow voters to rank candidates from first to last. To select the winner, Condorcet methods simulate multiple head-to-head elections. The Condorcet criterion proposes that the best candidate is the candidate which can win every single 1 vs 1 election combination. Take for example a three-way election with candidates Washington, Jefferson, and Monroe. For Washington to win, he must beat Jefferson in a one-on-one election, and then defeat Monroe in another one-on-one election. Condorcet methods compile ranking ballot data to instantly perform these one-on-one matchups. However, it is possible that no candidate is able to beat all other candidates. This scenario is called a Condorcet Paradox. The many variants of Condorcet methods use various algorithms to resolve Condorcet paradoxes. This report includes two ranked variants – Ranked-pairs and Smith-minimax.

Plurality – Plurality voting, or First-past-the-post (FPTP), is the current voting method used in most American elections. This voting rule is simple. You can only select one candidate, and the candidate with the most votes wins.

Score voting – Scored voting, or Range voting, is a simple system based on rating or grading candidates. For example, voters may grade each candidate from a scale of 0 to 5. To calculate the winner, the candidate with the greatest sum of scores wins. An example scored ballot is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 4: Ranked voting ballot used for IRV and Condorcet methods¶

STAR voting – STAR voting, or “Score Then Automatic Runoff”, is a variant of score voting with an extra runoff round. Score voting has been criticized by some voting theorists to be vulnerable to tactical voting. STAR voting was conceived in order to mitigate tactical voting concerns. As with score voting, two runoff candidates are chosen based on the sum of candidate scores. However, during the runoff phase, the final winner is selected based on the most preferred candidate. This runoff serves to encourage voters to express the full range of ballot ratings.

Top-Two Runoff – In top two runoff, the winner is determined from two-rounds of voting. The first round eliminates all but two candidates. The second round then determines the winner from the final two winners. For this report’s simulations, an automatic top-two method is employed using ranked ballots.

Majority Judgment – Majority judgment is another system based on rating or grading candidates. However instead of determining the winner from the greatest sum of scores (which is equivalent to the average score for each candidate), the winner is instead determined from the median score.

Smith-Score – Smith Score is a hybrid combination of scored voting and Condorcet voting systems. Smith score chooses the winner using a Condorcet-style selection as well as rated ballots. However, if a Condorcet Paradox is encountered, Smith-Score uses scored voting to resolve the paradox.

Election Model¶

Spatial Preference Model¶

A “spatial model” is used as the base of the simulation’s election model. The spatial model is a simplified mathematical representation of an election process. This model abstracts the choices of voters into “preference dimensions”. Spatial models have been used by many voting theorists, for example in Tideman and Plassman [2] [3].

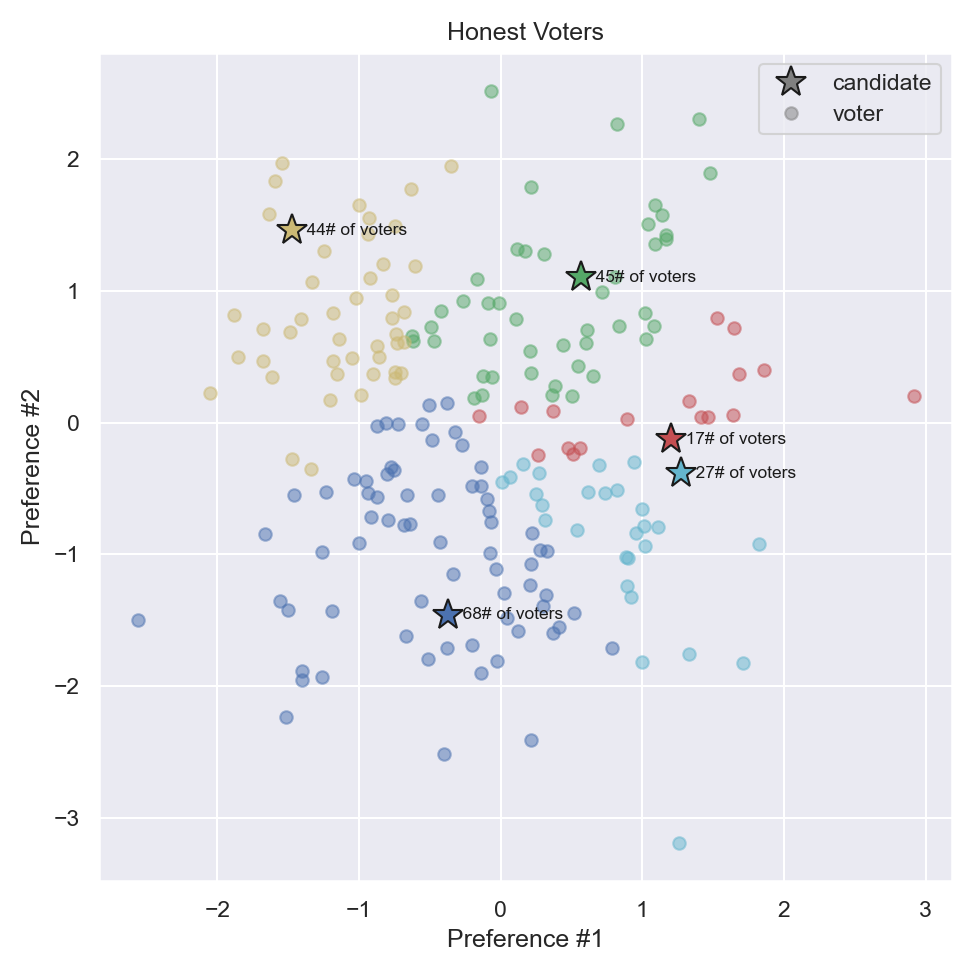

An example of a spatial election model is shown in Figure 1. In this model, voters and candidates are represented as points in space in two dimensions. These dimensions could be any arbitrary preference. For example, the preference could be the amount of money the voter wants to spend on the company party. Or, the preference could be a traditional political preference in the Liberal-Conservative spectrum. Or, the preference could be the desired rate of taxation.

Spatial models can be visualized for example in Figure 2. In this figure, a 2-dimensional spatial model is used. This model assumes that its voters care about two difference preference categories which are independent from one another. Alternatively, in a 1-dimensional spatial model, voters only care about a single preference category. In this model, voters prefer candidates who lie closer in distance to themselves.

Figure 5: Voters and candidate preferences in example spatial model¶

Model Parameters¶

Additional parameters of the model assessed are described in this section.

6000 total voter/candidate distribution combinations were simulated.

There are 51 voters for each election.

Spatial preference dimensions of 1, 2, and 3 were used.

Voter preferences are normally (Gaussian) distributed.

Candidate preferences are uniformly distributed +/-1.5 std deviations from the voter preference mean.

There are either 3 or 5 candidates in each election.

Voter Satisfaction¶

This assessment asserts that the candidate which minimizes the preference distance maximally satisfies the preferences all voters and therefore ought to be the winner of an election. In other words, the candidate which maximizes utility should win the election. In terms of geometry, this best candidate is the one closest to the centroid of the voter preference distribution.

To calculate the net satisfaction, a metric called “Voter Satisfaction Efficiency (VSE)” is used, which was devised by statistician Jameso Quinn.

Voter Behavior¶

Three assumptions of voter strategy were assessed in this report - Honest behavior, 1-sided strategy, and 2-sided strategy.

Honest Strategy¶

Honest strategy is defined to be a voter behavior where scores or ranks are constructed monotonically and proportionately to voter preference distance from a candidate. Honest strategy produces an “honest winner” for the election. For scored or rated ballots, honest voters in this simulation will normalize to give their most preferred candidate maximum score, and their least preferred candidate zero score.

Strategic Voters¶

Strategic voters are voters who predict the election outcome and then coordinate voting tactics on two front-runner candidates.

The “topdog” front-runner is the honest winner of the election. The “underdog” front-runner is an arbitrarily and iteratively chosen candidate in which a voting coalition is formed in an effort to defeat the topdog front-runner.

Strategic voters will always coordinate their votes to express maximum support for their preferred front-runner.

Tactics¶

Tactics are ballot manipulation routines voters may use to boost support for their preferred candidate. The assessed tactics include:

Bury – Rate or rank a front-runner the worst rank or rating equal to a voter’s true most hated candidate.

Deep Bury – Rank a front-runner the worst rank, below a voter’s true most hated candidate.

Compromise – Give a front-runner the best rank or rating.

Truncate Hated – All candidates equal or worse than the voter’s hated front-runner are given the lowest ranking or score.

Truncate Preferred – All candidates worse than the voter’s favorite front-runner are given the lowest ranking or score.

Bullet Preferred – The preferred front-runner is given the best score or rank. All other candidates are given the lowest rank/score.

Minmax Hated – Give worst rating or ranking to candidates equal or worse than a voter’s hated front-runner.

Minmax Preferred – Give worst rating or ranking to candidates worse than a voter’s favorite front-runner.

One-Sided Strategy¶

One sided strategy is defined to be a strategy where only supporters of an underdog candidate use tactics, while topdog supporters use honest strategy.

The goal of the assessment is calculate potential worst-case tactical scenarios, assuming rational underdog voters with perfect information. Given the enormous space of possible voter behavior, simulation post-processing chooses a one-sided tactic that must increase the satisfaction of underdog strategic voters but also minimize average voter satisfaction. Tactics are iterated over all possible underdog candidates and test against all possible underdog-against-topdog voting coalitions. Every listed tactic is iteratively tested. All underdog coalition members use the same tactic, though their ballot markings may still be different from one-another.

If all tactics backfire against the underdog (ie, result in reduced satisfaction for all underdog coalitions), then the honest election results are used. In other words, this analysis assumes that one-sided strategic voters are rational enough to avoid backfire.

Two-Sided Strategy¶

In two-sided strategy, underdog voters use the same strategy as in one-sided strategy. Topdog coalition members attempt to counter underdog strategy by bullet voting in favor of the honest winner.

In contrast to one-sided strategy, two-sided simulations do not filter out backfired two-sided tactics. Two-sided strategy tests a voting method’s ability to resist any sort of underdog manipulation.

For the scope of this assessment, no other topdog counter tactics were considered.

Comments on the Voter Strategy¶

Honest behavior represents an ideal where well-meaning voters do not try to take advantage of tactics. One-sided strategy represents the worst possible betrayal, where a candidate’s voters conspire against honest voters to maximize their coalition’s electoral impact. It is my opinion that one-sided strategic resistance is a very important trait for an election method to possess. If strategy is found to be highly effective, it would lead to greater and greater use of strategy.

It is also important to note that all tactics revolve around voter perception of who are “viable candidates”, which may or may not be based on realistic polling data. Obviously it is in the interest of campaigners to present false information so that a candidate is perceived to be “viable” and therefore worthy of applying tactical voting. The greater the tactical susceptibility of a method, the easier it is for campaigners to manipulate the electoral result.

Example Election¶

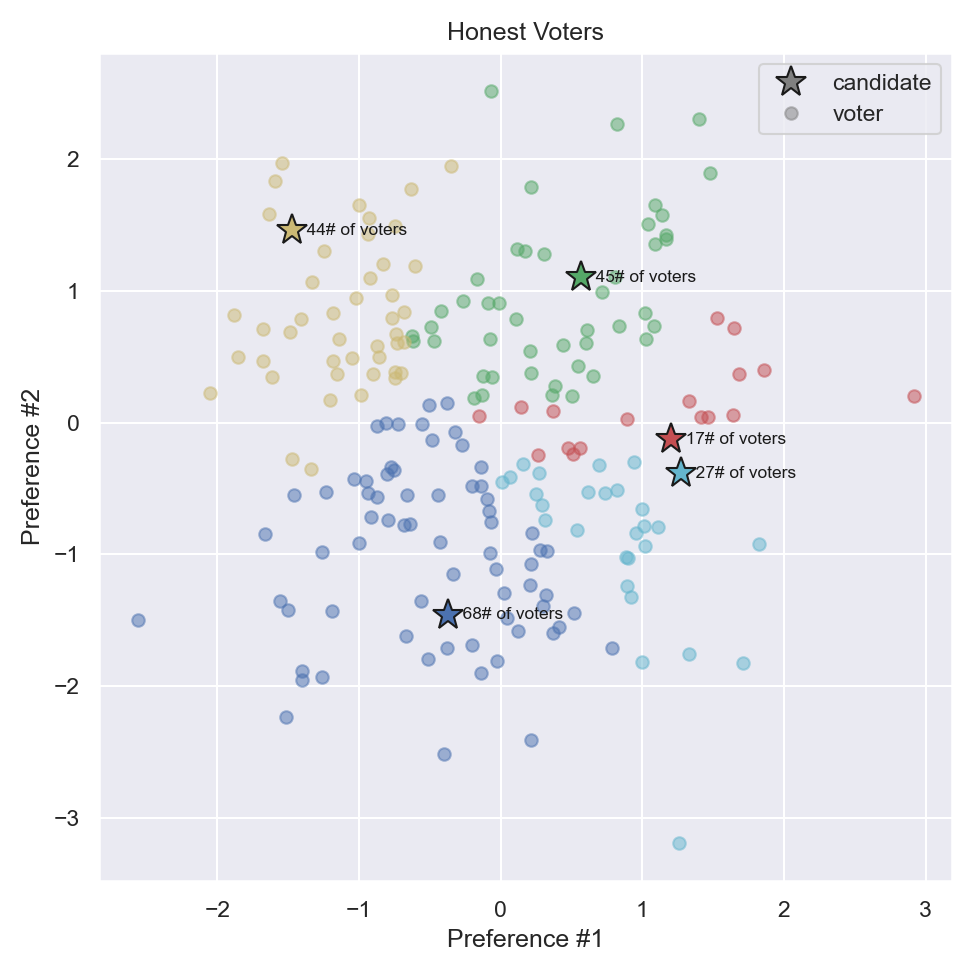

To illustrate the mechanics of tactical voting, a simple first-past-the-post plurality election’s results are presented in this section. This election was performed with 201 voters and 5 candidates. The results of an honest election are plotted in Figure 6. Candidate and voters are plotted in their 2-dimensional preference space. Candidates are denoted as stars, and voters are denoted as circles. Each of the 5 candidates is denoted Red, Blue, Green, Yellow, and Cyan.

In the honest election, the Blue candidate wins by plurality with 68 votes, or 34% of total votes. An honest election also results in a VSE of 0.83.

Figure 6: Voters and candidate preferences, assuming honest behavior¶

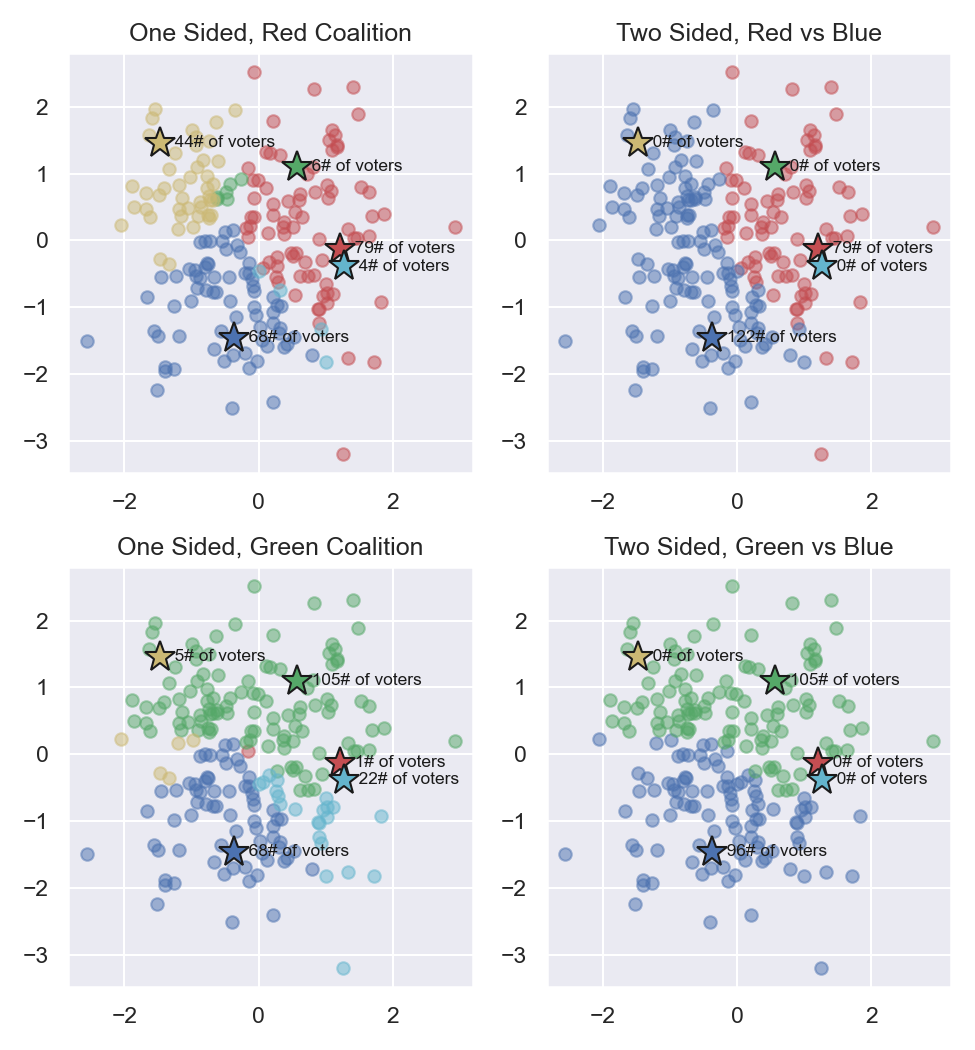

Clearly it is possible to form a coalition to defeat blue, yet which candidate should lead the charge? The next two Figures 7 and 8 propose a challenger coalition and observe the results.

Figure 7: Voter tactical preferences assuming a Red or Green candidate underdog coalition¶

In Figure 7 on the top row, a one-sided Red Coalition is capable of defeating Blue by 79 to 68 votes. In this strategy, the Red coalition decides to ignore Yellow, Green, and Cyan candidates. Non-coalition members that otherwise would support blue have wasted 44 votes on Yellow, 6 votes on Green, and 4 votes on Cyan. This election would result in 0.89 VSE which improves the results of an honest election. However in a two-sided struggle where a Blue Coalition is constructed, the Blue coalition can amass 122 to 79 votes, resulting in a Blue winner.

Figure 7 on the bottom row shows a potential coalition with Green candidate. In a one sided election, Green is capable of amassing 105 votes vs 68 votes for Blue. Moreover, even if Blue constructs their own coalition in a two-sided strategy, Green still wins with 105 against 96 votes. The Green-led coalition would result in a VSE of 1.00 which is the optimal result.

Figure 8: Voter tactical preferences assuming a Yellow or Cyan candidate underdog coalition¶

Figure 8 presents the potential coalitions for Yellow or Cyan candidates. Notably, it is possible for Yellow to defeat Blue 80 to 68 if a one-sided strategy is used. Such a combination results in the worst VSE of -3.09. It is also possible for Cyan to defeat Blue in a one-sided election by 77 to 68 votes with a resulting VSE of 0.36. However in both of these elections, a two-sided Blue strategy can resist these challenges to maintain a VSE of 0.83.

This simulator is interested in recording the worst case tactical results of an election. In our example, all four underdog candidates are capable of challenging and defeating the topdog honest winner in a one-sided strategy. The worst case scenario is a Yellow victory; therefore the one-sided VSE recorded for this election is -3.09.

One underdog candidate is capable of defeating the topdog honest winner in a two-sided strategy. The worst case scenario for this election however is coalition formation by the losing underdog candidates. Therefore a two-sided VSE of 0.83 is recorded for this election.

Results¶

The main VSE result is repeated here for 5th percentile, mean and 95th percentile VSE, given three different strategy assumptions.

Figure 9: Voter satisfaction efficiency for honest, one-sided, and two-sided strategy¶

Plurality voting is the most susceptible to strategic one-sided voting with a VSE of 0.19. In other words the resulting winner for one sided elections are closer to random selection than the VSE “Best winner”. Plurality overall has the worst VSE for honest, one-sided, and two-sided behavior.

Approval voting, score voting, and instant runoff also have mediocre strategy resistance with VSE of 0.51, 0.42, and 0.53 respectively. However their performance is substantially better than plurality.

High tier results are the Condorcet methods and STAR voting with one-sided strategy VSE ranging from 0.67 to 0.72. These methods in general also have high honest average VSE ranging from 0.95 to 0.97.

Based on these results, I recommend the replacement of plurality voting with any of the above tested voting methods, all of which are superior to plurality in the scenarios tested. However for optimal results, I recommend STAR voting or Condorcet methods.

References¶

Quinn, J. “VSE-SIM’. Center for Election Science. http://electionscience.github.io/vse-sim/VSE/. Accessed 6 June 2020.

Tideman, T. Plassmann, F. “Which voting rule is most likely to choose the best candidate?” Public Choice, March 2012.

Tideman, T. Plassmann, F. “The Source of Election Results: An Empirical Analysis of Statistical Models of Voter Behavior”. Journal of Economic Literature, June 2008.